Israel: IEI's Land Of Oil And Money

By: Joshua HammerIsrael may be the world's next energy superpower. But is this good for the Jews?

Illustration by Justin Metz

Illustration by Justin MetzOn a recent June afternoon, Bartov drives me to an overlook here, and points off in the distance, beyond the field of red peppers, to a shed half-concealed behind greenhouses. "That's where our pilot project will take place," he tells me. Some time in the next few months--barring bureaucratic delays or roadblocks thrown up by Israel's feisty environmental movement--Bartov plans to drill several wells into the bedrock here, going down 1,000 feet. His target: a potential mother lode of fossil fuels.

Bartov works for Israel Energy Initiatives (IEI), a Jerusalem-based startup with Goliath-size ambitions. In July 2008, the company obtained a license to explore 92 square miles of rural land in southern Israel. According to a 1980 study by the Geological Survey of Israel, the land may contain one of the world's largest deposits of kerogen-rich oil shale. Had the same rock been buried thousands of feet deeper, where temperatures range between 158 and 338 degrees Fahrenheit, it would have converted over millions of years into liquid crude. But no matter: In the past century, scientists discovered that by heating such rock to extremely high temperatures, they can transform the kerogen into oil--in effect, speeding up geological time.

Infographic: Oil Vey!

How much crude could there be here? Bartov and I drive from the Valley of Elah to a wheat field at the edge of a road near the town of Kiryat Gat. This is the site of one of seven exploratory holes that IEI has drilled over the past two years. The rock samples were analyzed by IEI chemists at Ben Gurion University in Be'er Sheva and at Weatherford Labs in Houston. Bartov says their estimates matched the company's "highest expectations"; if so, the equivalent of 500 million barrels of oil may lie beneath this wheat field. "What you see here would supply Israel's needs for five years," he says. And that's just a tiny percentage of the territory controlled by IEI. According to Bartov and other IEI geologists, oil-shale deposits in Israel could produce as much as 250 billion barrels of crude. That's roughly equal to the total reserves of Saudi Arabia.

IEI's leaders, including chief geologist Yuval Bartov and CEO Relik Shafir, believe they're on the verge of transforming Israel into an energy power. | Photo by Yoray Liberman

IEI's leaders, including chief geologist Yuval Bartov and CEO Relik Shafir, believe they're on the verge of transforming Israel into an energy power. | Photo by Yoray LibermanThe potential changes go beyond economics. With both Europe and the U.S. seeking to reduce their dependency on Arab-world crude, an oil-and-gas-rich Israel could arguably reshape the balance of power in the region. "Look at how Russia established its power in Europe and the world," says Gideon Tadmor, CEO of Delek Energy, an Israeli partner in the offshore gas fields. "Its clout is not due to weapons or military capability, but to its energy supplies." Dore Gold, Israel's former ambassador to the United Nations and president of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, says Israeli clout as an energy exporter could reshape Israel's relationship to Europe.

Significant obstacles stand in the way of this potential revolution. In January, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu drove legislation to end the country's dependence on oil by developing alternatives. More significantly, extracting crude from oil shale is difficult and fraught with peril. For nearly three decades, Royal Dutch Shell has been trying to heat shale below ground in Colorado, with limited success. A coalition of Israeli environmental groups has filed a lawsuit calling the project potentially hazardous, even though IEI's process is nothing like the oil-shale "fracking" that has riled U.S. environmentalists.

Israel's former UN ambassador, Dore Gold, says the discovery of oil could reshape Israel's relationship to Europe. Knesset member Einat Wilf agrees: "It could be a real game changer."

And yet, the prospect of all that oil and gas has begun attracting the attention of many big investors. Since the January 2009 discovery of the Tamar gas field, shares of Israeli oil-and-gas companies have soared. Last November, Rupert Murdoch and Jacob Rothschild, the British financier, teamed up to buy a 5.5% stake in Genie Oil and Gas Inc., the division of IEI's parent company, IDT, that holds its energy assets. Other investors and board members include former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney and hedge-fund billionaire Michael Steinhardt, who is now IEI's chairman. The infusion of cash has been a vindication for Bartov, a former research professor in Colorado, whose studies of oil shale were funded by Shell. "This deposit was known but neglected for decades," the IEI geologist tells me. "The right side of the brain knew, but the left side of the brain didn't connect. Nobody took it seriously. But that's changing."Harold Vinegar, the alchemist behind IEI's oil-shale project, holds up a glass vial to the late afternoon sunlight that pours through his office window in the hills of western Jerusalem. An ebullient man with a mad scientist's shock of white hair, he's showing me some fine-quality light crude that he distilled seven years ago, from Colorado oil shale. Like an oenophile, he swirls the translucent fluid. "See how clear it is?" says IEI's chief scientist, a Harvard physics PhD who was once the chief scientist for physics at Royal Dutch Shell.

For more than 25 years, Harold Vinegar extracted oil shale from Colorado rock for Royal Dutch Shell. Now, as IEI's chief scientist, he wants to do the same in, and for, his newly adopted country. | Photo by Yoray Liberman

For more than 25 years, Harold Vinegar extracted oil shale from Colorado rock for Royal Dutch Shell. Now, as IEI's chief scientist, he wants to do the same in, and for, his newly adopted country. | Photo by Yoray LibermanVinegar improved upon the Swedish results while working on Shell's fledgling projects in the Piceance Basin of northwestern Colorado, starting around 1980. Here, oil-shale deposits up to a thousand feet below the surface are thought to hold 800 billion barrels of recoverable oil--among the richest deposits in the world. Vinegar developed horizontal heaters that could generate high temperatures for months without burning out. With these, geologists could target the richest part of the oil-shale bed while leaving a minimal footprint on the surface. Heated correctly, the surrounding rock would take roughly three years for total molecular conversion of the kerogen into light crude. "After a few years of heating, the product was mostly clear," says Vinegar, who worked on seven Colorado projects for Shell over more than a quarter century.

The oil-shale industry in Colorado never really got off the ground. The high costs of heating and drilling wells made commercial oil-shale production unprofitable, especially when the price of oil fell. There were also environmental concerns, some involving the fact that the main aquifer in northwest Colorado runs through the oil-shale bed. While commercial production stalled around 1990, Shell has continued its R&D efforts there. Shell is now also taking its technology overseas. In August 2009, Jordan's King Abdullah granted the company oil-shale exploration rights to an 8,600-square-mile territory.

In October 2008, Vinegar retired from Shell. He and his wife emigrated to Israel, where he planned to take a teaching post. That really was the plan, he insists. But then Bartov, who had met Vinegar years before in Colorado, persuaded IDT chief Howard Jonas to ask the Shell veteran to bring his alchemy to IEI. Bartov was convinced that if anyone could get oil from the ancient shale in the Valley of Elah, it was Vinegar.

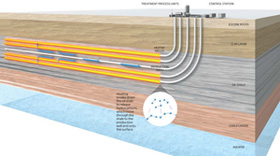

Turning Oil Shale

Into Oil

Harold Vinegar's oil-shale extraction process for IEI is nothing like the "fracking" that some U.S. states are trying to curb. Here's how it works:

Infographic: Turning Oil Shale Into Oil

Infographic by Bryan Christie Design

Above the Valley of Elah, Bartov walks me over to an outcropping that he says mimics the geological strata deep below ground. He points out a layer of chalk above a layer of porous limestone. The chalk is light and breaks apart easily, but it has small pores and low permeability, which keeps liquids from seeping through it. Beneath the earth, Bartov tells me, the chalk layer is 600 feet thick, forming an impermeable barrier between the oil shale above and the limestone below. So even though one of Israel's main aquifers runs through the limestone, this one is "completely isolated from the oil shale," he insists. "There is no danger," claims Bartov, that the groundwater will be contaminated by hydrocarbons expelled during the heating process.

Bartov and Vinegar promise that the heating process will be clean, energy efficient, and economical. Early on, IEI will heat the oil shale with electricity provided by natural gas, which is plentiful and cheap, and emits relatively low amounts of carbon dioxide. Eventually, says Bartov, electricity could be replaced by molten salt, a more energy-efficient technology widely used, above ground, in chemical and solar plants. By 2021, IEI could provide enough diesel and jet fuel from the Shfela Basin to cover Israel's military and civil aviation needs. After that, IEI would ratchet up crude-oil production to 270,000 barrels a day--the total amount of oil consumed in Israel--"if the country wants it," Vinegar says.

Exultant in his office in the affluent Tel Aviv beach suburb of Herzliyah Pituach, Delek Energy's Tadmor proudly claims that Israel has never been in such a strong position. Three years ago, Delek Energy teamed up with Yossi Langotsky, a pioneering Israeli geologist, and Noble Energy, a midsize American oil-and-gas company, to explore a tract of territory deep underwater in the Levantine Basin of the Mediterranean Sea. About 56 miles offshore, the tract was farther out than any ever plumbed by an Israeli company. But in late 2008, the partners began drilling the Tamar well--named after Langotsky's granddaughter--in 5,500 feet of water. Two months later, at a depth of 16,076 feet, they hit huge reservoirs of natural gas. Less than two years later, they found Leviathan, with an estimated 16 trillion cubic feet of gas--the richest offshore gas discovery of the past decade. The total value of the gas in Leviathan alone could reportedly reach an astonishing $95 billion. Tamar should begin producing gas in 2013; Leviathan will follow a few years later. Given that demand for natural gas is soaring following the disaster at Fukushima Daiichi, it should come as no surprise that Tadmor is sitting on a hot stock: Delek shares are up 987% since January 2009. "We are in the middle of huge change," says Tadmor, reflecting the prevailing view in Israel's energy community, "and it's a great opportunity for Israel."

It is a chance Israelis have been awaiting--even praying for--for more than half a century. As far back as the 1930s, in the decade before Israel became a country, British geologists searched futilely for oil and gas. When a team from the Lapidot Oil Co. and the Israel Prospectors Corp. finally did hit oil on September 25, 1955, the country's optimism was unleashed. "The energetic search for oil in Israel, carried on chiefly by American-financed corporations, marked its first success," reported the American-Israel Chamber of Commerce and Industry news bulletin. "Oil from the well gushed 65 feet in the air before it could be capped." The grade, the organization reported, "[was] better than average," and raised the hope "that eventually Israel will be able to meet its fuel needs from local sources."

Engineers and geologists searched everywhere for the next big strike. "The government supported oil exploration with good sums of money," says geologist Eliezer Kashai, a Hungarian who emigrated to Israel after World War II. But the Heletz-Kokhav field has produced just 17.5 million barrels of oil--less than Saudi Arabia produces in three days. Momentum petered out. For decades, the Israel National Oil Co. seemed a joke. Five hundred wells were drilled across Israel between 1960 and 1985, almost every one dry. In 1986, the national oil arm suspended drilling.

In the Bible, the Valley of Elah is the site of the battle between David and Goliath. Today, it's the site of a battle between IEI and the environmentalists who want to preserve its beauty. | Photo by Yoray Liberman

In the Bible, the Valley of Elah is the site of the battle between David and Goliath. Today, it's the site of a battle between IEI and the environmentalists who want to preserve its beauty. | Photo by Yoray LibermanAfter all this, the discoveries of Leviathan and Tamar seem like answered prayers. Yet, as the saying goes, be careful what you wish for. Israeli environmentalists warn that the natural-gas fields, which are being drilled under less stringent regulations than American sites, are a Gulf of Mexico–like nightmare in the making. "Aside from the Strait of Gibraltar and the Suez Canal, the Mediterranean Sea is a lake," says Dov Khenin, a Knesset member who is introducing legislation for stricter regulations on drilling. "If an environmental disaster happens there, we face a grave problem." Then there's the government of Lebanon, which claims Leviathan and Tamar extend into its own maritime borders; in the war of words between the two countries, the threat of actual war has been raised.

The biggest barrier to Israel's energy bonanza, however, is not geopolitics or technology; the true enemy of what has traditionally been seen as progress--a discovery of fossil fuels that might turbocharge the economy--is the country's own citizenry. Israel is something of a small village in global terms--you could fit 13 Israels into Colorado, despite Israel having 50% more inhabitants. But it is a noisy village, and many Israelis have raised rancorous opposition to IEI. They view IEI's project as a threat to their very lifestyles; they question everything that Vinegar, Shafir, and Bartov tout as benefits. In doing so, they raise interesting questions about drilling in the 21st century.

The day after my visit with Bartov, I drive back down to the Shfela Basin region and join three citizen-activists from Bishvil Adullam, a local advocacy group. We pass through a forest reserve called Britannia Park, filled with grottoes that protected Jewish warriors during the Second Jewish-Roman War, fought between AD 132 and 135. At the end of a dirt road we reach a different plateau overlooking the planned pilot project. "We don't want to be guinea pigs," says Chagit Tishler, a geologist who lives on a nearby moshav, a cooperative village, and who organized a December protest that drew 1,500 people. "There are so many uncertainties and unknowns. They are not being completely honest with us."

IEI's site is near a geological fault. If a major quake hits while the oil shale is being heated, says environmentalist Arye Wanger, "it could be like spilling a few tankers of crude" into Israel's main aquifer.

Tishler and other environmentalists, including Arye Wanger of the Israel Union for Environmental Defense, have a litany of fears. Tishler disputes the idea that a chalk layer will protect the aquifer. She believes pollutants will be expelled into the atmosphere during the refining process, despite the insistence of IEI officials that sulfur and other contaminants will be captured and managed. And she worries that oxygen could seep into fissures below the surface, ignite under extreme heat, and explode.Wanger, whose group has filed a petition with the Israeli Supreme Court to halt the pilot, questions virtually all the project data, because, he says, every qualified Israeli geologist is in some way connected to IEI. (The Geological Survey of Israel, for example, employs the country's best geologists; it is part of the Ministry of National Infrastructures, a strong backer of IEI.) He points out that the drilling will take place not far from a Rift Valley fault zone, which has experienced the effects of several moderate earthquakes in recent years. If a major quake hits while the oil shale is being heated, says Wanger, "it could be like spilling a few tankers of crude oil. It is simply not logical to allow a pool of oil above the major aquifer in Israel."

Most tangibly of all, Bishvil Adullam fears the oil wells, pumps, refineries, access roads, and other blight that comes with a booming oil-and-gas business. Its members don't want to see a pastoral corner of Israel transformed into an industrial wasteland. Tishler's colleague, Orit Skutelsky-Bahat, vows a campaign of civil disobedience if IEI moves forward. "We'll bring a lot of people here. We're going to sit on the ground, and they're not going to get anywhere," she tells me. "They don't have a chance."

Not a single claim of the pro-development faction is taken for granted in this debate. Government boosters such as Minister of National Infrastructures Uzi Landau contend that the new fossil-fuel finds will give Israel a geopolitical heft well beyond its minuscule size. And Einat Wilf, a Knesset member from Ehud Barak's newly formed Independence Party, says, "It could be a real game changer" in the United Nations, where the country can only count on the backing of one global power, the U.S.

Brenda Shaffer, an energy expert at the University of Haifa, finds such promises overblown. The experience of other countries with comparable amounts of natural gas gives her pause. "Azerbaijan produces a lot more gas, but their conflict with Armenia hasn't been resolved," Shaffer says. "Gas flows from Egypt won't preserve peace with Israel. Libya brings more gas to market in Western Europe than Israel ever will, but that doesn't mean that NATO won't bomb it." Only the powerhouses in natural gas, Russia and Saudi Arabia, have translated economic might into political muscle.

Like many natives, Shaffer wonders why Israel needs fossil-fuel development at all. The country has vibrant tourism and thriving high-tech and bio-med industries; it weathered the 2008 global recession far better than most developed nations. "Still, [some officials] are saying, 'We want to be Saudi Arabia,' " she says. "I look at Saudi Arabia's low education [rates], and lack of democracy, and think, Why would you want that? This oil will not change anything in a good way."

"We are a country where everybody knows everybody," says Wanger, "where environmentalists can talk to ministers, to members of parliament, and express our views. That's the good thing. On the other hand, the economic forces here are very powerful, and I wouldn't gamble on the final result. It's going to be a hard battle."

In April, IEI celebrated a partial victory: The Israeli Supreme Court tabled a petition by a coalition of environmental groups to stop the pilot wells, agreeing only to hear the case before a full body of three judges in April 2012. In the interim, the court said, the pilot may move ahead as planned. Still, IEI faces numerous bureaucratic delays. The company hopes to drill three 1,000-foot-deep wells 3 meters apart from one another, and heat the rock for 270 days as part of a demonstration project that would produce 2,000 barrels of crude oil a day. But even though IEI has obtained the license necessary for drilling, it cannot move ahead until it gets a land-use permit from Israel's minister of the Interior. And the final go-ahead won't come just from that ministry, but in concert with a district planning and building committee that includes representatives of local communities and officials from the Ministry of Environmental Protection.

"We don't think the environment ministry wants this project to happen," says Bartov with frustration. "By killing this kind of project you are not advancing the world's green-energy research." The ministry has not yet issued an official position. When I ask Bartov how long he thinks it will be before the pilot starts, he shrugs. "I never believed this would be so difficult," he says. "I thought people would be thrilled."

Vinegar is willing to be patient; the oil shale, after all, is not going anywhere. Besides, IEI's chief scientist has a vague sense that his project may even have been sanctioned from above. "Deuteronomy has a section about the tribe of Asher, where it says, 'and you shall produce honey from the rock, and oil from the flinty rock,' " he tells me. In the Shfela Basin, he points out, "there is a 2-meter-thick layer of flint that just runs continuously. How could they possibly have known that? How could they have?" Vinegar cackles. "It's just spooky."

A version of this article appears in the September 2011 issue of Fast Company.